Ricardo Gomes Moreira, PhD candidate in anthropology

Institute of Social Sciences, University of Lisbon

Ancestry has become, in the last decades, a central concept in human population genetics. On this notion stands genetic perspectives about the origins and history of contemporary living populations. However, ancestry has several meanings and outside of genetics, the idea commonly informs practices related to identity, kinship, and family history. Hence, in the last two decades, genetics, identity, and history have become increasingly interconnected, since genetic knowledge is now also taking steps to inquire about the origins of human groups, their genealogical connections, as well as the history of population movements, migrations, and encounters.

The word “ancestry” derives through the ancient French form ancesserie (that which is related to the ancestors), from the Latin root antecessor: he or she who antecedes, who “has gone before”; those “who quitted/ abandoned before” (ante + cede). The ancestors are thus, not only those who departed but also those who yield to us their legacy. From those who came before us, we inherit something that we will, in turn, cede to those who will come after.

Ancestry is a relation of intergenerational linkages, connecting an individual to their predecessors by means of something which is inherited through those linkages. That which is passed over from those of earlier generations to those of later ones is, therefore, what produces the ancestry relation: that legacy or inheritance is the fundamental property of ancestry, defining its quality and its own rationality. Ancestry relations can assume, therefore, diverse forms according to that which is inherited, or to what someone who came before relinquishes to those who will follow. Ancestors and descendants are thus connected by these transmitted legacies. Thus, the variability of what can be deemed as ancestry relations is concomitant to the variability of qualities assumed by the legacies of previous generations to the present and future ones. In fact, these legacies can be seen as configuring several types and exhibiting different natures: they can encompass linguistic or cultural forms and traditions, systems of symbols and beliefs, religious or juridical norms, rules and taboos, property, offices, social positions and status, scientific legacies – as inscribed in the genealogies of knowledge systems and disciplines –, as well as biological or genetic traits – as is the case with the idea of genetic ancestry inscribed in the intergenerational reproductive transmission of DNA.

Ancestors and Ancestry in anthropological literature

Writing in 1986 about kinship, the eminent anthropologist Jack Goody noted the following about a universal character and general importance of ancestors in human societies worldwide:

«Ancestor worship had been seen by a number of earlier workers in comparative sociology as the elementary form of the religious life, but it was also central to Freudian interests in anthropology, and this encouraged [the search for] connections with the elementary forms of kinship. … [This book] is perhaps the most sensitive and sophisticated analysis yet made of a feature which, often in the more generalized form of the cult of the dead, is found so widely distributed in human societies. § The link between one’s relations with parents and with ancestors, […] was at the same time a link between kinship and religion as well as between anthropology and psychology» (Goody, 1987: 8).

Goody, Jack (1987), “Introduction”, in Meyer Fortes, Religion, morality and the person: essays on Tallensi religion. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

“Cultural practices” addressing the forebears of a certain group or community have been described and analyzed by anthropologists since the early days of the discipline in the mid-19th century. Through direct or indirect action in the present world of the living, departed ancestors were presented as taking part in the everyday lives of their descendants. While ethnographic studies concerning beliefs about the actions of deceased ancestors became examples of what could be named as “anthropology of religion”, ancestors’ role as sources of meaningful symbologies and cultural legacies around which group identities were formed became one of the main topics of mainstream socio-cultural anthropology. Kinship was, therefore, a core theme of anthropological research connecting all fields of religion, politics, and social organization. Ancestors’ cults, descent groups, lineages, and kinship systems formed, up to the 1970s, disciplinary main frames of anthropology that were, most of the times, essentially concerned with rural or local communities living at the margins of modern states and their industrial and monetarized economies. In these classical ethnographic fields, relations with the ancestors were deemed by anthropologists to be of the utmost importance for the maintenance of the social order.

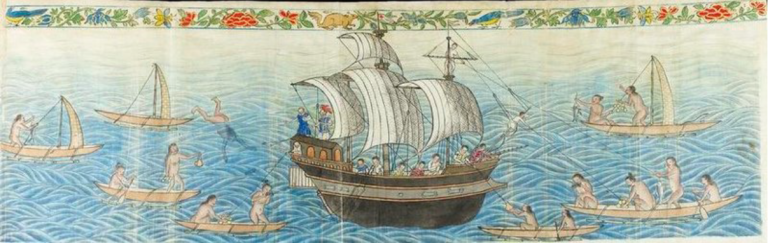

Figure 1 – Schematic representation of clan dynamics and structure of descendants typical of mid-20th century social anthropology. Source: Fortes, Meyer (1967), The Web of Kinship among the Tallensi.

The second post-war era, however, brought with it several unsettling social changes, and in such a way that the sciences of the social would also be transformed in the process. Decolonization movements led to the emergence of newly independent nations, setting off new industrial economies and urbanization processes. In relation to massive global migrations from different countries and rural communities into growing cities – accompanying industrial and technological intensification – urban populations reached new magnitudes of density and diversity. In urban landscapes made from the aggregation of domestic and international migrants, the cults of ancestors tendentially lost some adherence to other forms of rituality and belonging.

After the 1970s, classical anthropological studies of kinship and descent systems lost some of their grip in the discipline, and the ethnographic descriptions of these ancestors’ cults were often replaced by different accounts of other forms of collective rituality seen as more relevant in societies of continuous change and transformation. Anthropological knowledge also became more urbanized and “relations with the ancestors” were increasingly replaced, in anthropological literature, by other forms of “modern” identity such as “ancestry relations”, which are the topic of the second part of this brief essay.