Cristiana Bastos

University of Lisbon, Institute of Social Sciences

CB: Patricia, thanks for having us. Your Fulbright and CUNY awarded Research Project Galleon intersects with our project Ancestry in that, it critically revisits some of the Early Modern maritime travels and analyzes some of the interactions between newcomers and residents in the islands we now know as the Philippines. Can you tell us a bit about the project? First, how did you conceive this project? What were the leads that brought attention to the role of women in the predominantly male universe of Spanish Conquistadores?

PT: Thank you. This project is part of a much larger exploration that looks at the history of women during the Spanish Conquest and the Age of Discoveries. I have been researching this topic, for several years now. I am finishing a book, tentatively titled “chronicles of Ancient Women of the Indies. Part I: The Other Side of the Ocean, and Part II: ‘Terra Firma.’ The idea began when I was researching the topic of gender and science, looking at women as voyagers, the history of geography and anthropology, and the idea of travel. I noticed that women tended to be overlooked and left out of official narratives of discovery and travel. When I talk about my research, many people are surprised, because they assume that women were never part of this history. When I tell them that there were many, then they ask me if “they were prostitutes.” It is a terrible and widespread stereotype. Once you start looking for women, you find them everywhere. They are mainly in the archives, they wrote letters, and were recorded in many ways; chroniclers and early historians wrote about them. So, they exist and have moved long distances, crossing continents and oceans. The purpose of my trip to the Philippines was to search for the women who were part of the three hundred years of the Galleon trade. I was affiliated with the National Museum of the Philippines which offered me generous help. I could see first-hand the artefacts recovered from several shipwrecks, including the San Diego which was sunk by the Dutch, near the Fortune Island in Batangas, in 1600. This was a fully laden vessel containing all kinds of luxurious objects such as Chinese Ming pottery, religious images in ivory, jewellery, and many other things that are displayed in the Museum in Cebu. My project gives great attention to the objects that traveled both ways, and were appropriated by the people in Spain, such as the famous “Manton de Manila,” a garment used in Flamenco dancing by women, and a symbol of Spanish identity, or the “Mexican rebozo,” some with Asian Ikat designs, imposed by priests to cover Indigenous women entering churches. Curiously a municipality in Mexico, known as Santa Maria del Rio, calls itself, the “Cradle of the Rebozo,” and is situated near the mining town of San Luis Potosi. This particular town sent most of its silver production to China and other parts of Asia, in the returning galleons. In Mexico, people still eat mangoes Filipinos, and go to cockfights, imported from Asia. Another interesting example is the “filipina” or “guayabera,” or “Camisa de Yucatan.” Some people say it is Cuban, but the interesting thing is that King Felipe of Spain has donned this shirt on his recent trips to Mexico and Cuba.

CB: And what have you found so far about the role of women in the transoceanic travels?

PT: I have found many fascinating things. For example, Magellan’s wife, Beatriz Barbosa, gave him her dowry, so he could navigate the world. There is a document in the Archive of Indies requesting the devolution of his money to her since those who returned from the first circumnavigation of the world had brought spices and other wealth. Since the time of Columbus, women were in his navigations; there were thirty women in his second voyage. Later, we find them as passengers, as owners of ships, as cargadoras, who provided the food, and stores for the trips, as governors, and administrators. In 1514, in the fleet of Pedrarias Davila to Santa Maria la Antigua, there were three widows, we only have the name of one, Viuda de Collantes. They sewed the sails for the 19 vessels, and they were in charge of linens and other necessary items for the first hospital in Terra Firma. Columbus married in 1479 a Portuguese woman, Filipa Muniz de Perestrelo, and travelled with her to Porto Santo; she was the daughter of Bartolomeu Perestrelo, the governor of the island. Filipa gave Columbus her father’s maps and other documents and instruments, and it was in Porto Santo that he developed his idea of going west and returning east. Columbus and Filipa had a son, Diego, born in Porto Santo, who was appointed later as 2nd Admiral, and Governor of the Indies. His wife, the noblewoman Maria de Toledo, had the title of Vicereine, and, later, the first female Governor in the New World. This couple owned the first sugar plantations in Santo Domingo and were owners of the first slaves directly imported from Africa. The first slave rebellion in the Americas took place in 1521, on their plantation. The ruins are still there and now are declared Patrimony of Humanity by UNESCO.

There were many other influential women. The list is long. Maria Niño de Rivera, widow of King Ferdinand’s secretary, controlled gold production and became extremely rich selling soap and candles to people in the New Colonies. In 1556, Mencia de Calderón travelled with a group of 80 young women who had been promised as future brides to Spaniards who were building settlements in Asuncion, Paraguay, and needed European women in their colonies. The trip lasted more than six years after they had all kinds of adventures, including being imprisoned by the Portuguese in Brazil.

I also want to mention the case of Isabel de Barreto, who earned the title of First Admiral of the Sea. In 1595, Isabel, her sister, and a group of women sailed from Peru, with Isabel’s husband Alvaro de Mendaña.

Portrait of the Venerable Mother Jeronima de la Fuente Yánez by Diego Velásquez, 1620, Prado Museum, Madrid

Isabel was left in charge of the expedition when Mendaña died at sea. They reached the Marquesas and the Salomon Islands, and finally, they arrived in the Philippines. She stays there for a while, gets married again, and returns to Mexico in a Galleon full of rich cargo. There were also the cases of nuns who founded convents and contributed to the spread of Catholicism. One of them was Sor Jeronima de la Asuncion, immortalized by the painter Diego Velazquez, who travelled to Manila with 10 other religious women, in 1620, at 65 years of age to establish the Santa Clara convent, the first in Asia. They endured all kinds of hardships for four months in the galleon that took them from Acapulco to Manila, witnessed the cruel punishment of a black enslaved woman, and were finally carried by natives in hamacas, during the last leg of their journey. There are many examples, and if we look for them carefully, they will be revealed to us.

CB: How does an anthropologist trained in ethnographic fieldwork work through Early Modern sources? How do you articulate archival work and field visits?

PT: I have called my work an ethnography of the archives and other written sources and modern representations of the conquest and colonization. We have to understand that those sources are extremely biased, written by people who wanted to gain something, and who were always in a position of privilege, trying to glorify themselves. We have to read beyond that and analyze it in different ways, if possible, from the perspective of the subordinated native. I have travelled to many of the locations where the events of conquest happened, and have been collecting the local interpretations in the form of murals, monuments, and other narratives. That in itself provides great information about how the past is recreated and reinterpreted. For example, this is a picture I took, in 2015, in Santo Domingo, the first city in the New World. Native, Taino women are highly sexualized, never in resistance poses, in many representations of the past, just as Dominican females are today.

Photography taken by Patricia Tovar on a street in Santo Domingo, Dominican Republic, 1915.

CB: What have you learned so far regarding the actual life of the populations under the Spanish rule in the Pacific?

PT: My project has taken me to three interconnected countries this year. Since the Philippines was a province of Mexico, there is a great influence in terms of culture, language, and food. For Spaniards, the Philippines is like any other ex-colony. There is an Instituto Cervantes in Intramuros and another in the fancy area of Makati, next to important embassies. But they have exposure in museums and archives, there is a Metro stop in Madrid, called Filipinas, and buildings have names such as Mindanao or Mindoro. I had a similar impression in Mexico. The Philippines were not very important in the construction of the modern nation, and the galleon trade ended with Mexico’s independence from Spain. But, for the Filipinos, both Mexico and Spain continue to be present in many ways. The country suffered greatly during the US regime, and more during WWII and the Japanese invasion. Spanish colonial areas were destroyed, including the walled city of Intramuros in Manila, which also witnessed several horrifying massacres and abuses, and the sexual exploitation of women. Chinese merchants, converted to Catholicism, were providers of goods for the galleons, but they were kept outside of Intramuros, within the watchful eye of the Spaniards. This a vibrant community, a tourist spot, but unfortunately, it is surrounded by slums, and highly polluted waterways. You can walk around some of the old streets of the “Pearl of the Orient,” as Manila was called before the war. In the somewhat run-down Escolta Street in Binondo, a district of Manila, you could still see the faded beauty of timeworn buildings. And there are ancient, stunning churches everywhere in the Philippines, built by the Augustinians, some in ruins, and others in good standing. There are some towns in which you can appreciate a blend of Spanish, Chinese, and Filipino colonial architecture, with huge translucent windows adapted to the tropical weather, as in Vigan in Ilocos Norte, and Taal in Cavite province, near the point of departure for the Galleon trade, in Manila Bay. Many towns and streets continue to have Spanish names. There are many streets named Magallanes all over the country, the most important, and prosperous, is in Cebu, known as the “Heart of Commerce.” In Cebu, there is a shrine and a Minor Basilica, dedicated to the Señor Santo Niño, a miraculous and widely venerated image, given to Magellan to Princess Juana, formerly known as Humamay, the first baptized person in the Philippines. To commemorate the event, and to show the beginning of Christianity in Asia, the Magellan Cross is planted in the shrine. Forty-four years later, when Legazpi arrived to stay in the country, legend says, that the image of the Santo Niño was found in the ruins of a house in Mactan, and the relic survived to this day. There is another important image there; Our Lady of Guadalupe of Cebu, patron saint of the Philippines, a cult brought by the Mexicans.

I took this picture at the airport in Cebu. Colorful dancers carry the Santo Niño.

Finally, I found the place where the Santa Clara convent of Sor Jerónima stood in Intramuros, sadly a parking lot now. The Clare nuns still exist today, but they were moved to Quezón City. There is a sizable population of Muslims, or moros, as they are called, in Mindanao, in the south. They had been there before the time of Magellan’s arrival, and they continue to be struggling for independence. There is an area in Mindanao, called Zamboanga, where a Creole language with great Spanish influence is spoken. I wanted to visit it for my research but was advised against going there. And let’s not forget, that Filipinos have Spanish surnames, given to them by the colonial administrators, as a way to control them better.

Today, the Philippines remains in many ways a scarred and traumatized country, that is still trying to come to terms with the legacy of colonialism, and struggling to overcome the infamous internal corruption that has created great inequalities. Wealth and abject poverty coexist side by side, and unfortunately, there is no sign that this will change any time soon.

CB: What modes of memorializing encounters between the Spanish envoys and local populations have you encountered so far? How do narratives of conquest, subjugation, and resistance interplay with one another? Can you provide some examples (e.g., the events of Cebu in which Magellan lost his life)?

PT: We can start with the case of the Dominican Republic, where colonialism began in the Americas. We have to look at the monuments and see who built them and for what purposes. Many monuments are being decolonized in many former colonies, and history is being reinterpreted in many ways. The Haitian historian Trouillot talks about this in his acclaimed book “Silencing the Past.” That was exactly what the dictator Trujillo did in the country. His narrative was extolling the civilizing effort of the Spaniards, as welcome and necessary for the progress of the nation. The “Columbus Lighthouse” a cross-shaped building, a mausoleum that they argue, contains the ashes of Columbus. A situation in which the good native is always in a subservient position, looking up at the Spaniard, as their saviour and protector. In the Philippines, I encountered a different narrative. A narrative of resistance against European invaders. Lapu Lapu, (sometimes spelt as Lapulapu) the warrior who killed Magellan is a national hero. The place in Mactan is considered a shrine, sort of like a religious pilgrimage site. In this image, Lapu Lapu gives its back to the monument to “Hernando de Magallanes,” Gloria de España, built in the same place by Isabel the Second, in the 19th Century.

These images were taken by Patricia Tovar from the Shrine also known as Liberty Shrine, in Mactan in October 2023. The stone monument in the back is dedicated to Hernando de Magallanes, in 1866, “Reinando Isabel II, and on the other side it says “Glorias Españolas.” The monument seems run-down and is missing something on top.

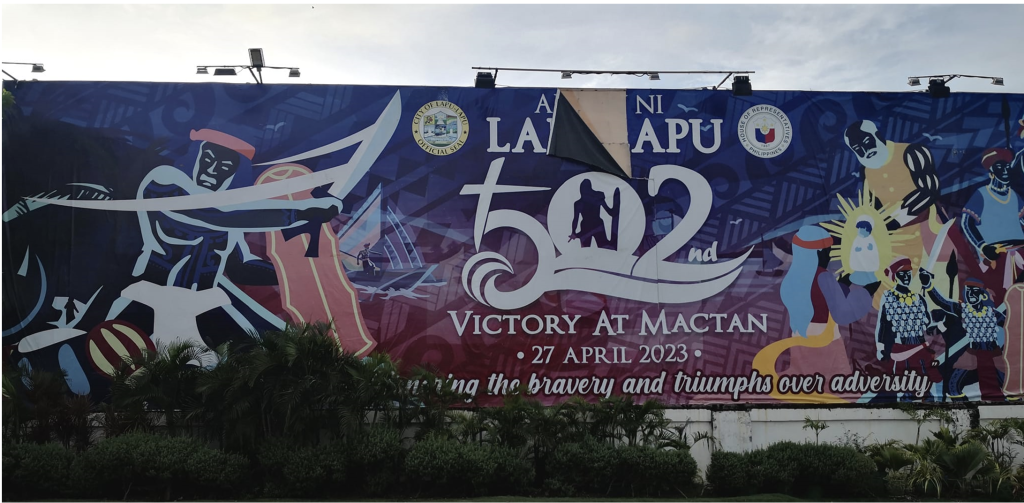

But the most common image of Lapu Lapu always depicts him about to kill Magellan, as in the case of a painting in a corner of the shrine. There is also a big illuminated billboard, commemorating 502 years of that victory, April 27, 2023.

The most common image of Lapu Lapu always depicts him about to kill Magellan, as in the case of a painting in a corner of the shrine. There is also a big illuminated billboard, commemorating 502 years of that victory, April 27, 2023.

The arrival of Legazpi, years later, in 1565, is portrayed as a peaceful “Blood pact” as they call the monument in the Visayas. A pact among friends and equals with Rajah Sikatuna in Tagbilaran, and for a short period, Cebu was the capital of the East Indies. With Legazpi, arrived a group of Mexican indigenous Tlaxcaltecas and criollos who will help in the “civilizing” effort. They found the Portuguese trying to blockade them from controlling Cebu. Legazpi arrived with Fray Andrés de Urdaneta, who would eventually find the elusive route to return to Mexico, through the Pacific, away from treacherous currents, establishing trade with the Manila Galleon. Now, this is the part that I am researching now, about the presence of women in this period. So far, I am intrigued by mentions of a mestiza girl, Grace, Urdaneta’s daughter, from his time in the Spice Islands, before becoming a priest, and that he took with him to Mexico.

My picture of the Blood Compact Monument in Tagbilaran honoring the first treaty of peace and friendship between the Philippines and Spain.

Finally, the new narrative by artist Kidlam Tahimik, exhibited at the National Museum, offers a reinterpretation of history which is considered subversive, and feminist. Tahimik advances the theory, that maybe it was Princess, Lapu Lapu’s wife, Princesa Bulakna, who gave the final blow to Magellan.

Image from the National Museum of the Philippines in Manila taken October 2023

In this image “Nuestros filipinos civilizados,” Our Civilized Philippinos, Tahimik, in addition to the reference to Christianity, is alluding to the infamous 1887 Expo in the Retiro Park in Madrid. This racist and colonial exhibition brought to Spain a group of 43 Filippino natives (naturales) from different ethnic groups and exhibited them in a human zoo. They were separated as “civilized” or Christianized, and “uncivilized.” The women were displayed rolling cigars and weaving textiles.

Thank you.