Ricardo Gomes Moreira, Ph.D. candidate in anthropology

Institute of Social Sciences, University of Lisbon

Ancestry in population genetics: a sociological angle on the relations between human biology and identity

In the last decades, the idea of “ancestry” has become one of the most important and popular notions in human population genetics. On this notion stands genetic perspectives on the origins and history of contemporary living populations. However, ancestry has several meanings and outside of genetics, the idea commonly informs practices related to identity, kinship, and family history. Hence, in the last two decades, genetics, identity, and history have become increasingly interconnected, since genetic knowledge is now also taking steps to inquire about the origins of human groups, their genealogical connections, as well as the history of population movements, migrations, and encounters.

As a concept used to address genealogical identities and relations of common descent that can be discerned in genetic analysis, ancestry has been simultaneously used to evoke the origins of individuals or populations in terms of their genealogical past, but also to bestow a sense of genetic or biological identity.

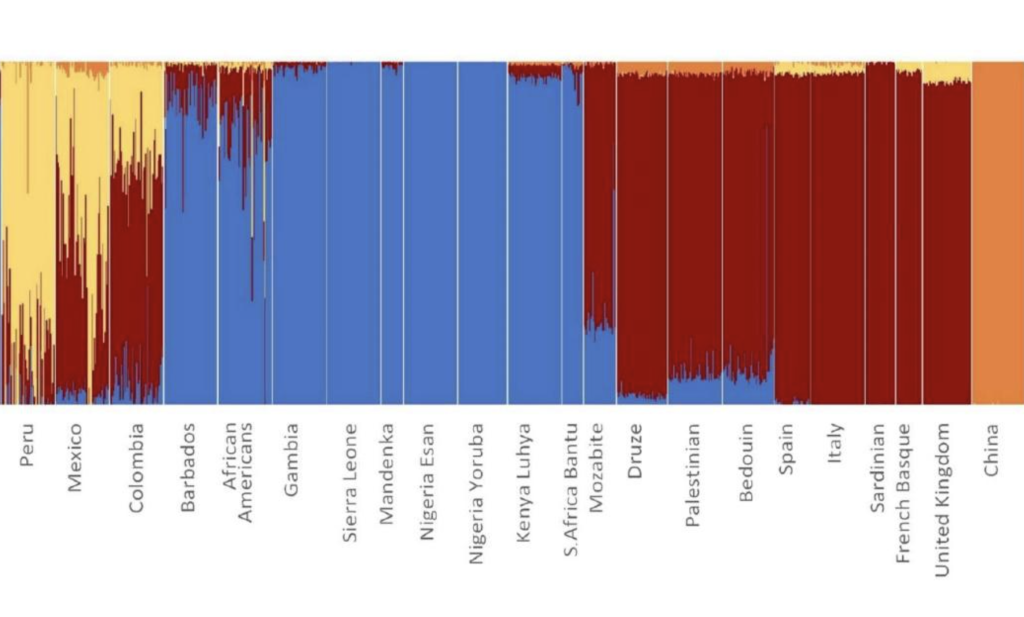

The identity dimension inscribed in the idea of ancestry is paramount. While sociologically ancestry is part of a person or group’s identities in relation to narratives about their past, in biology it is applied to “genes” or, more precisely, to biomolecular configurations. However, while being detected by analysing the sequence of bases in the DNA molecule (or in other types of the biomolecular composition of the human body), these ancestral genetic geographical identities are seldom applied to the molecular configurations themselves. Instead, ancestral genetic identities are assigned to individual bodies and consequently interpolated to the population level. At the collective population scale, ancestry is made up of the aggregation of each one of those single individual ancestries, forming a composition of collective ancestry profile under specific identifying labels denoting, most of the times, sociological entities: ethno-linguistic groups, geographical regions, nationalities and so forth. The biological or genetic identities can be, therefore, juxtaposed with those sociological identities emerging from socio-political contexts and dynamics.

Still, while scientific uses of genetic ancestry are crucial in contemporary population research, facilitated access to genetic surveys by both public and private laboratories, has made “genetic ancestry” a commercial product as well. Presenting them as “ancestry tests” under several different trademarks for those seeking to uncover their origins, companies offer a service that is conceived and marketized to exploit the common human drive for belonging and recognition, i.e. the “identity” dimension present in our sociability. Through genetic tests, anyone can buy a knowledge of their “true identity”, within global historical and biological narratives of the human species. In this sense, “biological identity” equates to an idea of ancestry that is more about “from where” our ancestors come from, than about “who they are”. Consequently, “ancestry” as a biogeographical category is quite different from the notion of “ancestor”, the latter pointing to one or more individuals whose names and history may be known to living generations and around whom family histories, memories, and myths are formed. If, on the one hand, ancestors can be named and recalled as founders of lineages, family identities, clans, or kinship groups, on the other hand, ancestry is here a more generic instance of belonging, in which the connecting links to the past are created through genes, and people are more often associated with places than with specific families or “historical” figures. Genetic ancestry is, therefore, assumed to be a biogeographic ancestry.

Figure 1 – Representation of four different categories of biogeographic ancestry in different populations. Each vertical line represents an individual genomic analysis (African ancestry in blue, European ancestry in red, Native American ancestry in yellow, and East Asian ancestry in orange). Source: Sierra, B. et al. (2017), “OSBPL10, RXRA, and lipid metabolism confer African-ancestry protection against dengue haemorragic fever in admixed Cubans”, PLOS Pathogens, 13 (2). (Cropped image from the original).

Notwithstanding, connecting people to different places of origin that are labelled as geopolitical entities (nations, regions, ethnicities, countries, or sub-continental regions) has been seen by some as a re-evocation of the kind of partitioning that was (and still is) the fundamental rationale for “racial differentiations” among the human species, linking biological characteristics, geographies, and specific ecological environments. Moreover, the fact that ancestry tests were developed as a commercial product in America – where the idea of “obsession” was used to describe Americans’ conspicuous interest in genealogical research – and the fact that “genetic ancestry” services became a successful business among “New World” populations – where racial identities have explicit social and political significance – is not a coincidence. “Genetic ancestry” seems to assume particular relevance in those contexts where racial categories are also of greater socio-political pertinence, either as a form of identity and community belonging or as part of inclusion-exclusion criteria in public policies, as is the case in the “multi-ethnic” or “multi-racial” cities of the USA. Because, as is often stated by geneticists, genetic ancestry is about “who we are and where we come from”, and that is what identity is about after all.