artist, researcher, educator, PhD in cultural sciences

The Ancestry Traveller project is my second meeting with high-tech sequencing and reading genetic information. In my synthetic motherhood project, I have been co-working with a forensic lab to predict the future look of my potential offspring. Ancestry testing allows us to do something opposite, to read the past (at least to a certain extent).

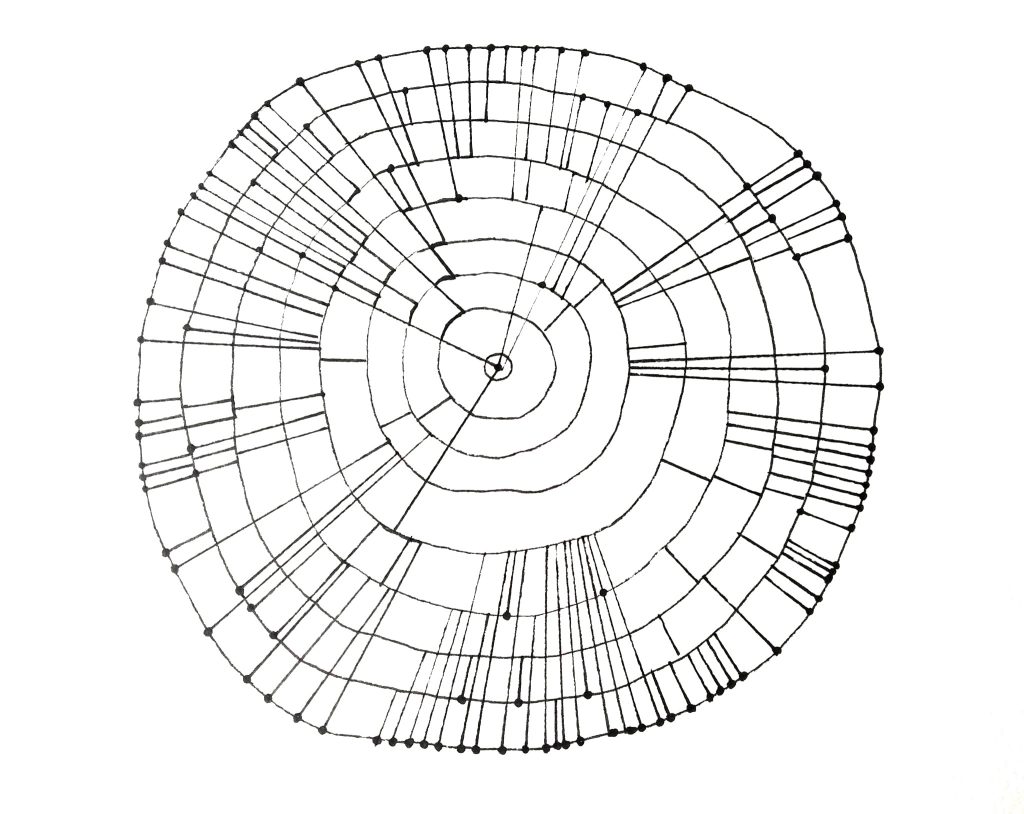

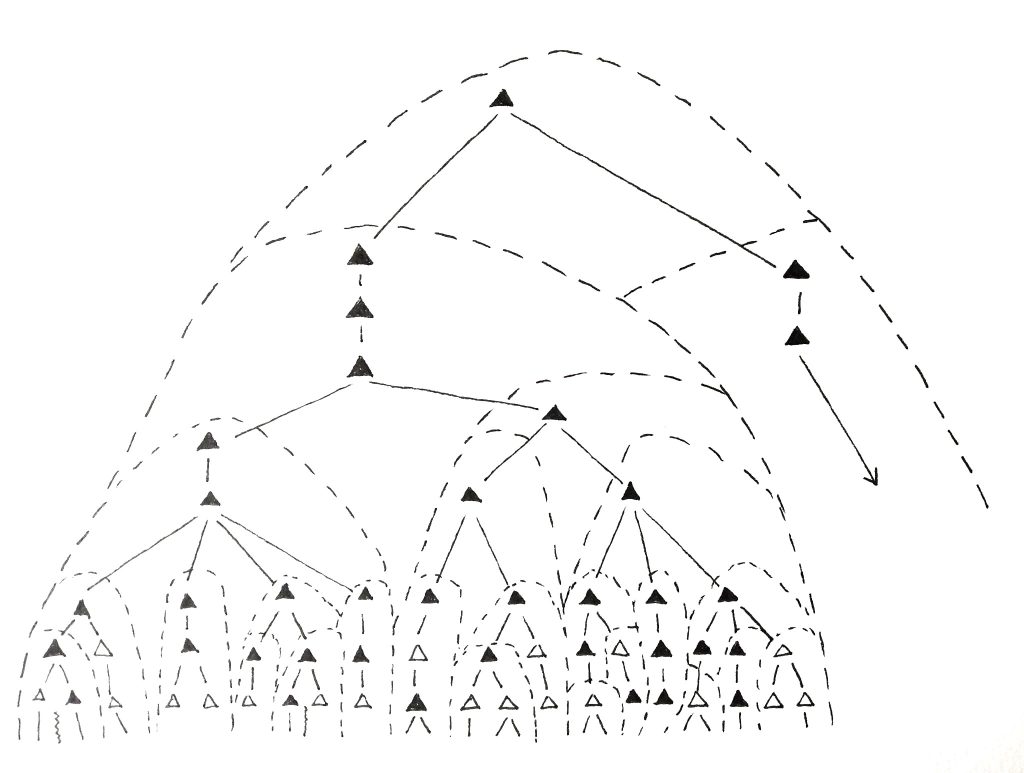

Drawing by Karolina Żyniewicz, based on a scientific paper, black ink on paper

It is a very intriguing idea to invite 12 artists to be in dialogue with geneticists working with ancestry testing and science communicators trying to explain the research genre to the broader audience. The main questions that appeared in my mind after I got accepted for the project were:

What is my role in it?

Am I supposed to support science communication?

Should I be a translator of complex scientific data?

I like these uncertainties and find them inspiring. They are not related only to this particular project. They are essential to art & science in general.

After participating in two intense workshops prepared by the project organizers and run by Prof Luísa Pereira, researcher and group leader of the Genetic Diversity group at i3S, and getting the results of my ancestry test, I noted the following thoughts which drive me in my further work:

- Human population genetics is a very specialized area of research. It is tough to simply “jump in” from a different area, like art, and be able to read the scientific data (connect dots). Another complication is that we can’t work on our samples ourselves (it is too expensive) to understand the process better.

- The scientific data (schemes, numbers) are very abstract. What is needed here is a form of junk art (Bardini, 2010), art that requires a narrative explanation. Building a narration around the data takes a lot of intellectual gymnastics. Something like removing the scheme descriptions and enjoying their graphic, and visual values is much easier. However, is that art that satisfies us?

- The social aspects of population research and its historical roots are much more helpful in creating artistic narrations than the “naked” scientific data.

- Artists tend to be subjective and build individual stories about reality to share and confront them with others. It is very challenging to do it based on the ancestry test report. Who were our ancestors actually, and how did they travel and create families? Does my genetic GPS tell me I should behave like those living in that location, sharing their values and cultural patterns? These questions remain without answers. We got some information, but are they useful for us as individuals? Should we expect them to be useful for our individual life trajectories?

- The DNA samples, in our case, saliva, usually look identical until they spoil. Then they can differ in color and transparency level but become useless for scientific examination. The difference in the sample appearance at a specific moment does not reduce our equality in the face of biological destruction and death.

- Ordinary people (I mean here, everyone who does not work with population genetics) are often interested in doing ancestry tests because they hope to discover that they are somehow different from the majority, somehow unique. It is usually disappointing to find that we are very similar, like the DNA samples given for the investigation.

Schemes without written information. Drawings by Karolina Żyniewicz, black ink on paper

I am inquisitive if the other artists participating in the project have similar thoughts. The intellectual exchange between artists, scientists and science communicators in the project framework can bring fresh and intriguing discoveries.