Cristiana Bastos

University of Lisbon, Institute of Social Sciences

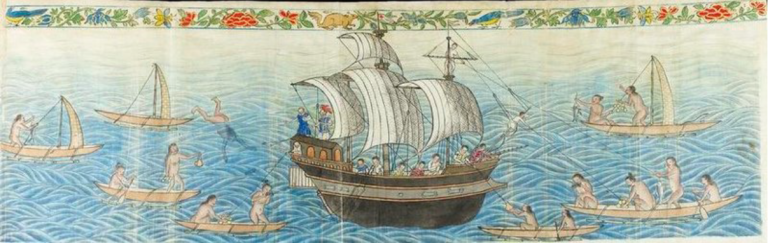

Magellan. Portugal, Torre do Tombo, SNI, Arq. Fotográfico, n.º 68760

In August 1519, a five-vessel armada departed from Seville, sponsored by the Spanish King Carlos and commanded by the Portuguese-born Ferdinand Magellan. Like Columbus before them, they tried to reach the East via the West. They had a mission: to reach the Moluccas and its spices without crossing the areas controlled by the Portuguese. Several years and many adventures and misadventures later, the sole remaining ship returned to Seville, now commanded by Juan Sebastian Elcano. Magellan had died along the way. The remainder of the fleet and crew arrived from the East, thereby completing the first circumnavigation of the world. They also brought a cargo of spices that was meant to cover the expenses of the entire endeavour. What had been the purpose of the voyage: the circum-navigation, or the spices?

The purpose of the voyage, we know today, was not the one that made it famous, that is, the circumnavigation of the globe. Such was a notorious consequence of a voyage meant to reach a less notorious goal: to open for Spain a maritime route into the distant, desired, and lucrative spices of the Moluccas. At that time, Portugal and Spain were the most powerful empires and divided the world between them so that they would not compete with each other for influence over territories, oceans, routes, commerce, and other imperial purposes. They agreed on a dividing line – the Tordesilhas meridian. To its west laid the sphere of Spain’s entitlement, corresponding to most of the Americas and the Caribbean, and its east was Portugal’s sphere, corresponding to the entire coasts of Africa and Asia, plus a slice of South America that would be the embryo of Brazil. Under that treaty, the Portuguese, and not the Spanish, had access to the trade in the Indian Ocean all the way to Southeast Asia, including the Moluccas and their cloves, nutmegs and mace. But what if there was a way for Spain to avoid the Portuguese waters, going westwards, beyond the Americas, all the way to the Spice Islands? And, even more interesting, what if the counter-meridian proved that the Moluccas fell on the Spanish side of the world? Those were the arguments used by Magellan to persuade the Spanish King Carlos into supporting his very daring endeavor of reaching southeast Asia navigating westwards, hoping to find a passage across the Americas, all through the so-called Spanish half of the world.

World Map of Cantino, 1502, with the Tordesilhas Meridian (Museu Esteense de Modena; image from National Geographic https://www.nationalgeographic.pt/historia/o-atlas-que-foi-desenhado-por-um-portugues_3439)

Clove (Syzygium aromaticum) and Nutmeg and Mace (Myristica fragrans). Handcoloured copperplate engraving after a botanical illustration by Christiane Henriette Dorothea Westermayr from Friedrich Johann Bertuchs Bilderbuch fur Kinder (Picture Book for Children), Weimar, 1792.

Magellan knew well the Indian Ocean; he had served the Portuguese Crown in India and Malacca; his good friend Serrão was himself in the Moluccas. Unhappy with the slim acknowledgement and short rewards given to him by the Portuguese King, Magellan offered his services to the King of Spain – and was successful in that purpose. He was granted command of a well-equipped armada of five ships – Trinidad, Victoria, San Antonio, Concepcion, and Santiago. Most of the officers were from Spain, some were from Portugal, sailors were from everywhere, and the chronicler was Italian. Throughout the voyage, there was no shortage of political disputes in which Magellan’s loyalty to Spain was questioned. Tensions peaked in San Julian, leading to a mutiny, months before they reached what would become the Strait of Magellan. Stefan Zweig, Magellan’s most intimate and in-depth biographer, tells us about those poignant days and their difficult circumstances, which led to the sacrifice of at least one of the officers.[1]

Antonio de Pigafetta, the chronicler of the voyage, spares the details – perhaps to minimize the role of Juan Sebastian Elcano in the revolt, for Elcano would be the one to complete the circumnavigation voyage by bringing the remaining vessel Victoria to Spain, across the forbidden waters under Portuguese control in the Indian Ocean and the coast of Africa.[2] But the circumnavigation came later, after Magellan died on the island of Mactan, nowadays the Philippines. Previous to the passage of the strait that got Magellan’s name, tensions ran high and the commander was constantly on the lookout. He was fixed on finding the passage – the physical passage and the pathway to the desired riches, the profits of the Moluccan spice trade, the honours, the recognition by royals, and perhaps the rights a part of the islands he assigned to the Spanish crown through the voyage of “discoveries.”[3] Behind this complex and long voyage that became the first circumnavigation of the globe, there were many contradictory motivations and endless misunderstandings.

[1] Zweig, Stefan, Magellan, Translated by Cedar Paul, London, Pushkin Press, 1970.

[2] Pigafetta, Antonio, The First Voyage Round the World & al., translated by Lord Stanley of Alderley (Hypertext).

[3] Fernandez-Armesto, Felipe, Straits. Beyond the myths of Magellan. Berkeley, U California Press, 2020.